Vaginal prolapse in cows

Keywords: bovine, vagina, prolapse, pregnantThe first image show a vaginal prolapse in a polled Hereford cow. This cow had been affected during her previous pregnancy but despite a recommendation to cull her from the herd, she was re-bred after that calving, The fluid streaming down on either side of her tail is povidone iodine, used after shaving, to prepare for epidural anesthesia.

Image size: 1740 x 2070px

The role of relaxin in vaginal prolapses has not been adequately addressed.

In affected cows, edema and (probably) hypertrophy of the vaginal mucosa, cause it to become so swollen that it cannot be contained within the vaginal lumen. The tissue mass then prolapses to the exterior. The presence of a swollen mass in the vagina causes straining and exacerbation of the edema. The prolapse may sometimes expose the cervix but surprisingly, ascending placentitis and abortion is rare. Involvement of the bladder is seldom mentioned in discussions on vaginal prolapse but this is known to occur. Trans-mucosal ultrasonography would be useful to exclude that possibility.

Below: A severe vaginal prolapse in a Brangus cow that was approximately seven to eight months pregnant. A thick cord of mucus, similar to that seen before normal calving, is hanging from the cervix.

Image size: 1000 x 1373px

Courtesy: Dr J. D. Smith, author and holder of copyright: Smith@cvm.msstate.edu

In rare cases, the prolapsed tissue may become severely traumatized and necrotic, threatening the life of the cow.

Vaginal prolapse does occur in dairy cows but is predominantly a condition of beef cows and especially Bos taurus ss indicus breeds. Among Bos taurus breeds, Herefords appears to be most commonly affected. It has been stated that polled Herefords are more often affected than horned Herefords but this author was unable to find information to substantiate that. Although one would presume that vaginal prolapse is more common in older cows than younger cows because their vaginal adnexa may be more flaccid, first-calf cows are commonly affected.

The role of poor body condition in prolapsed vaginas is not clear but some consider it important.

In the benchmark publication of Woodward and Quesenberry in 1957 a comparison of genetically different Herefords managed under similar management suggested that vaginal prolapse has a heritable basis. A genetic link is also substantiated in finding that this condition is so much more common in some beef breeds than others and as mentioned, is rare in dairy cows. In some beef herds it may affect less than 0.5% of cows, in others, 2 to 3%. Therefore it is strongly suggested that affected cows should not be re-bred after calving and their calves should not be used as herd replacements.

The image below shows a mature Brahman cow in late gestation; presented after a failed attempt to retain a vaginal prolapse using nylon sutures. The remnants of the suture can be seen in the photograph on the right. Because of her poor body condition and prohibitive cost of a cesarean section, the cow was euthanized.

Image size: 1000 x 1373px

Courtesy: Dr John Cavalieri, author and holder of copyright: john.cavalieri@jcu.edu.au

The image below shows a truly unusual case of a prolapsed vagina in a Hereford cow. This cow has two cervices, the result of incomplete fusion of the caudal section of the mullerian ducts. See more on that condition in another LORI entry. In this case, the calf (inset) was delivered through the left cervical canal. It is not known if the right cervical canal was patent.

Image size: 1500 x 1030px

Courtesy: Dr C. Austin Hinds, author and holder of copyright: ahinds@uidaho.edu

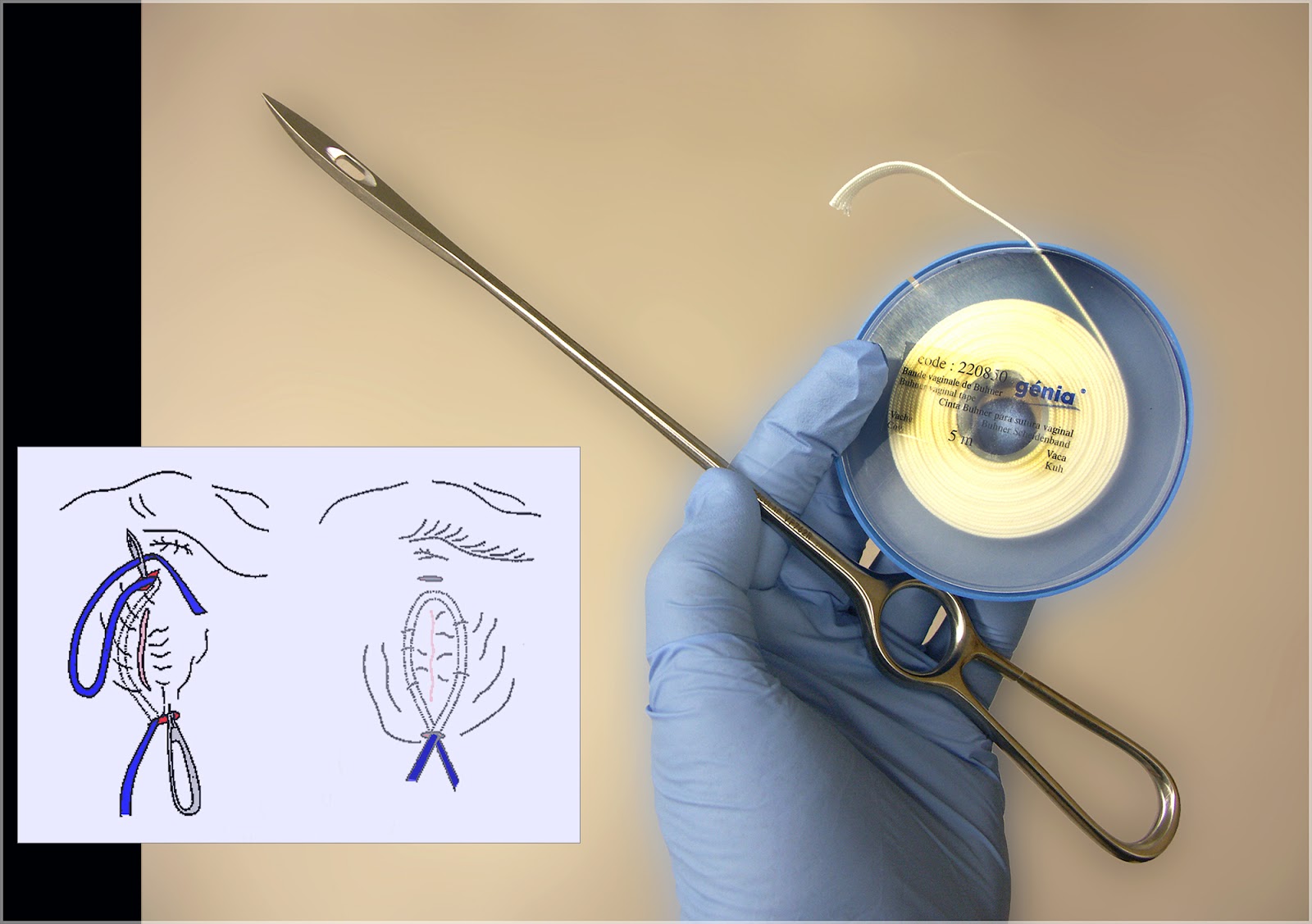

There are many approaches to the treatment of vaginal prolapse but the most common, is probably the use of a Buhner needle and tape to place a perivulvar purse-string suture. After epidural anesthesia, a small incision is made dorsal and ventral to the vulva as shown in the inset. The tape is fed through the perivulvar area, deep in the adnexa and tied in a bow at the ventral vulvar commisure. The purse string is closed down over three fingers, enough space for the urination. When the cow shows signs of impending parturition, the bow is untied.

Image size: 2000 x 1409px

Inset image courtesy of Dr Ronald Trengrove of Pretoria, South Africa (contact details on demand), modified by the author.

The following three images are the property of the author and holder of copyright: Mr Donald Crawford, senior student (2014), Onderstepoort Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pretoria. South Africa: dc_crawford@hotmail.com.

In the first image, after application of epidural anesthesia, the washed prolapsed mucosa is gradually being compressed and pushed cranially. This author prefers to wrap a hand towel around the prolapse to facilitate compression. To avoid traumatizing the vagina, it is essential that patience be exercised during this process.

Here, the vaginal mucosa has been compressed sufficiently to return it to the vaginal lumen.

The author wishes to thank colleagues in the ACT for their collective experience, discussion and contributions to this entry in LORI.

References:

Drost, M. 2007 Complications during gestation in the cow. Theriogenology.68:487–491

Woodward, R. R. and Quesenberry, J. R. 1956 A Study of Vaginal and Uterine Prolapse in Hereford Cattle. J.Anim Sci.15:119-124.